Bulgarian Protein Crops – have a bright future, despite price fluctuations

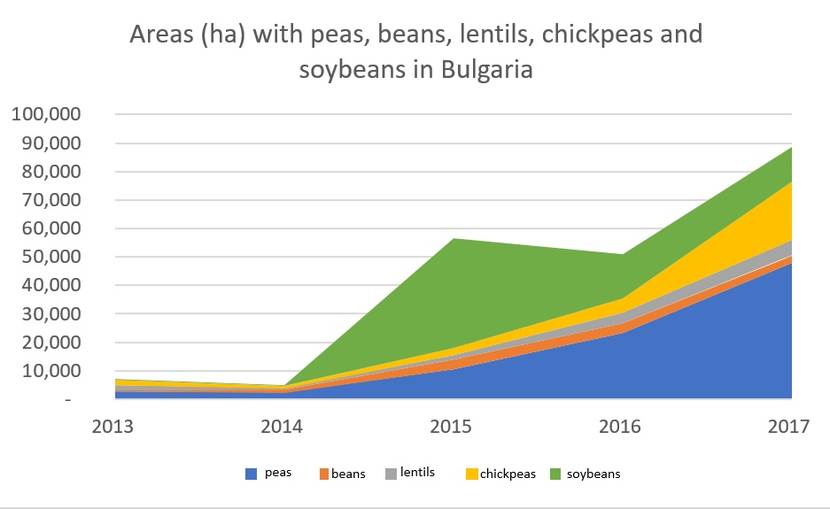

The areas of peas, lentils, beans and chickpeas in Bulgaria grow rapidly, driven by “green” requirements, additional subsidies and ... the market. The question is for how long?

One of the obvious trends in native farming over the last five years has been the increase in the area and the production of protein crops[1]. While soybeans are disappointing with the results and purchase prices, farmers are strongly relying on peas, chickpeas, beans and lentils. The reasons for this are at least three: with the introduction of so-called “green payments” in 2014, producers have been able to meet the requirements for obtaining them by sowing protein crops (first); namely, protein crops, unlike other options for implementing green payments (e.g. fallow or grass mixtures that have other manufacturing weaknesses), provided them with an additional subsidy, initially of BGN 28/dca, which subsequently fell to BGN about 20/dca (second); the prices of most grain legumes promised a good return (third). If we add to this the proven link between leguminous crops and soil fertility, the benefits of producers choice seem to be indisputable to date. Which of the growth factors shall prevail in the long run, however?

The Bulgarian producers “have been touching” the soil during the first two years of the new 2014-2020 programming period, wasting between different protein crops, setting aside fallow areas and sowing grass mixtures. Gradually, however, they “picked out” the pulse of the market and started relying on larger areas of grain-leguminous crops. This was also aided by the market conjuncture, which provided between BGN 50 and BGN 200 net income per hectare (without taking into account the rent costs and subsidies received).

Policy and support

The “green” requirements introduced by the latest reform of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy are here to stay. There are enough indications that, although they are necessary, the current requirements in the First Pillar will serve as a basis for the new CAP architecture after 2020. Strategic environmental targets will be set at EU level and Member States will have much greater freedom in the measures to reach the targets at regional level. Accordingly, the use of protein crops to meet the requirements and additional support for them may also appear a matter in which the national decision will be crucial.

An unexpected shock to protein crops came from Brussels’ decision to ban the use of pesticides in the Ecological Focus Areas (EFA). The inspection in Bulgaria will be documentary and it is more than clear that not all manufacturers will comply with the ban. However, the potential economic losses in leguminous cropping due to the inability to maintain adequate plant protection may in the long run undermine the incentives for farmers to diversify their production.

At the same time, the benefits of including protein crops in crop rotation appear to be indisputable – both from agro-ecological and from market perspective.

Protein deficiency

With the population growing on the ground and the purchasing power of larger parts thereof, demand for protein will grow. But striving for healthier nutrition will also play a role in this process with the desire of a growing population in developed countries to limit the consumption of animal proteins. Legumes have a protein content equivalent to that of meat and are a much cheaper source of protein at a times lower ecological footprint. For this reason, the forecast for the global development of the protein crop market is to increase it with an average annual growth rate of 5% over the next five years. Prospects for protein crops are particularly good in Europe, where plant protein deficiency is enormous (ranging between 70-80% over the last 40 years[2]) and is mostly satisfied with imports of GMO soybeans from North and South America. Providing GMO-free protein of native origin (which will also reduce the carbon footprint) is an obvious opportunity for targeting for the next programming period.

Fluctuating market

As more recessing (at least relative to other cereals) and with relatively low production costs, legumes often suffer from sharp price fluctuations. Any market signal that crops are lagging behind in consumption is an incentive for producers to rapidly increase their area, which inevitably leads to price adjustments.

The forthcoming 2018/19 is likely to be the case for some of the legumes, which is also supported by political decisions in important trading regions of the world. Climate problems in some major global producers in the past two years have prompted a significant increase in the area. This growth was centered on both world leaders in manufacturing (e.g. Canada, USA, Australia) as well as relatively new players such as Eastern Europe and Kazakhstan, where legumes grew extremely fast in two or three years.

Increased production has led the largest consumer and importer of legumes – India to levy 50% of the import of peas and 40% of chickpeas and lentils in an attempt to protect their domestic prices. These restrictive measures taken at the end of 2017 already reflect the market.

Canadian supplies of pea instantly declined by 22% at the end of the year. The accelerated increase in production in Eastern Europe (Russia and Ukraine) has placed 655,000 tons of grain on the market, which easily undercuts Canadian peas by USD 25-45/ton. In 2018 Russia is expected to reduce the area of peas, but the transitional stocks in Canada are set at an impressive 915,000 tons.

Kazakhstan is becoming an increasingly serious lens manufacturer – in just two years, the country's territory has grown tenfold to 331,000 hectares. Production in the country is expected to double. In 2017 it reached 300,000 tonnes, of which 70% were exported (mainly to Turkey, and less to Iran, Azerbaijan and Afghanistan). Restricting imports from India will leave Canadians with 810,000 tons of transient stocks, but a problem with the realization is more likely to be found in red lentils that are much sought after to produce different curry. The brown and green lenses are still trading well.

Chickpea found an excellent market ahead of 2016-2017 because of the Mexican harvest problems. High purchase prices have led Canada to increase production by 20% and the US – five times. Meanwhile, Mexico has restored its production last year and is expected to double it in 2018. All this has led to a 40% drop in the price of chickpeas on the world markets by 40% from USD 1543/ton to USD 882/ton last year. From zero, the world's transient stocks in the current marketing year reached 180,000 tonnes and a new price downturn can be expected with certainty.

Although there is a turbulent year for the legume markets, long-term prospects remain good. The question is for each farmer to judge for himself which crops are suited to his conditions and can bring him a long-term slightly higher profitability. Of course, it is also necessary that the policy in the sector be conducted in a planned and consistent manner.

[1] For the needs of the present work, as well as in terms of market specificity, here we deal with grain-legumes. No grass crops, such as alfalfa, clover, etc., are also included, which areas also grow.

[2] OCL 2014, 21(4) D403

Source: InteliAgro based on SFA database