Cocoa processing in Côte d'Ivoire: What will the added value be?

What are the potential consequences when cocoa processing is done in Côte d’Ivoire? Finding an answer to this question was the main objective of a recent analysis carried out by Metabolic – one of the Dutch frontrunners in the world when it comes to systems thinking*. Find out more in the article below written by the Metabolic.

In the project ‘Together towards local cocoa transformation’, Metabolic applied systems thinking to the value chain of cocoa between Côte d’Ivoire and the Netherlands. In systems thinking, we focus on the ways in which the individual parts of a system relate and affect each other. It is a powerful tool to identify potential leverage points, the points within a system where action has the biggest impact.

The aim of this project was to gain insight into the ways in which collaboration between the two countries could contribute to a living income among cocoa farmers. The objective of the project tells us which topics were of particular interest; supporting the transition to a more fair and sustainable cocoa industry in Côte d’Ivoire, contributing to living income and the position of women and youth in the industry, and exploring circular and local initiatives within the value chain.

Analyzing material flows

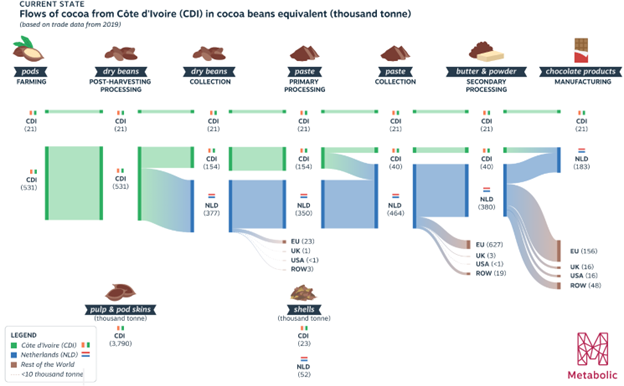

The main tool guiding this project was a Material Flow Analysis (MFA), which is a methodology that produces an overview of the inputs and outputs of a system. An MFA was done for the current state of the cocoa value chain between Côte d’Ivoire and the Netherlands, following the processing steps from the farm gate to the end consumer. This analysis shows that the majority of cocoa is exported from Côte d’Ivoire as raw beans, and that the Netherlands is the most important trade partner for Ivorian cocoa (24% of all exports). Additionally, it shows that many processing steps take place in NL, and that a large volume of waste products remain in Côte d’Ivoire without being used, such as pulp and skins.

A subsequent analysis shows the distribution of added value between both countries. From this chart, it is clear that most of the added value is captured upon exporting cocoa powder and butter, which takes place in the Netherlands. We can conclude that more value is captured in the Netherlands (24% more), and of the value that does get captured in Côte d’Ivoire, only a very small portion goes to the cocoa farmers

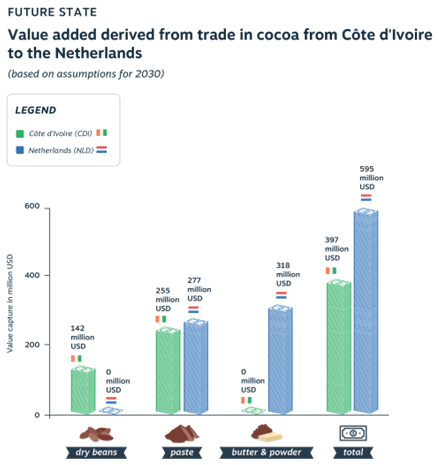

With this in mind, the Ivorian government wants to promote additional processing to take place in Côte d’Ivoire, before exporting. Specifically, they want to process 100% of cocoa into cocoa paste by 2030. This idea is based on the assumption that it will raise the added value captured in Côte d’Ivoire, thereby supporting the local economy and contributing to living income among farmers. This new system is expected to have an impact on sustainability in the industry, and affect the country’s trade partners.

Envisioning future material flows

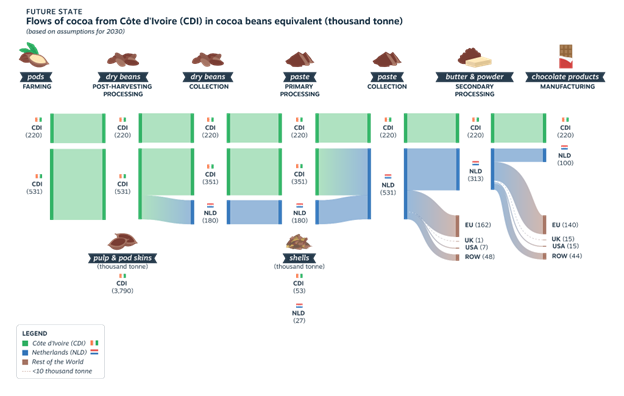

To better understand the impact of this plan, we conducted a similar analysis for the future state of the cocoa value chain. Extensive quantitative as well as qualitative research was done to build the assumptions underlying this forecast.

Looking at the results for 2030, we see that there would be significant changes in the trade patterns. Obviously, the majority of cocoa export would be as paste, and the export of beans would reduce strongly. The Netherlands would remain Côte d’Ivoire’s largest trading partner, but interestingly, a greater volume of Ivorian cocoa would reach Ivorian consumers due to trade regulations on deforestation and local government efforts to promote local consumption.

Where is value actually added?

We also looked into the distribution of added value in this future state, and this reveals some interesting results. The majority of added value is still captured in NL, and the imbalance even grows in the favor of NL. We did not find a straightforward explanation for this outcome, but there appear to be two important factors. First, the international cocoa trade and its infrastructure is currently set up to facilitate the existing trade patterns, in which producing countries export beans. Importing and processing countries like NL will continue to have demand for beans, rather than paste, to keep their industry going. As such, the value of paste is not significantly higher than that of beans. A second factor is that, currently, most of the price premiums on quality or certifications are targeting beans, rather than paste

Unexpected effects

By looking at the value chain as a system and considering how its different parts relate and function, this analysis predicts that the plan of Côte d’Ivoire to promote processing into paste before export, may not have the desired effect.

Once we had come to this result, we explored ways in which additional value could be captured within Côte d’Ivoire, as well as create social and environmental impact. We examined the models that are currently being used to promote local processing. There are two popular models;

- one is a commercial, export focused model,

- the other is a community model, focused on local markets.

These models further differ in the products they produce, the actors involved, the objectives and the level of scale.

Striking the balance to serve the living income of farmers

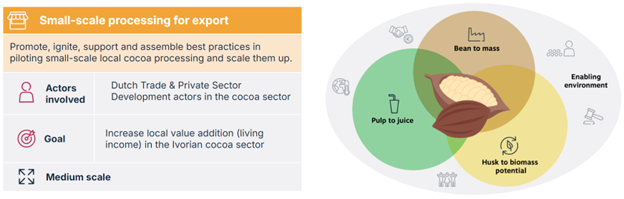

The recently launched Orange CocoaPro programme promotes a new, third model, combining the export of cocoa paste with the use of waste streams to produce products for export. Examples of the latter are the production of cocoa pulp based drinks (like Kumasi) and the use of waste streams as biomass. This model aims to support living income among farmers, as well as create wider economic, social and environmental impact

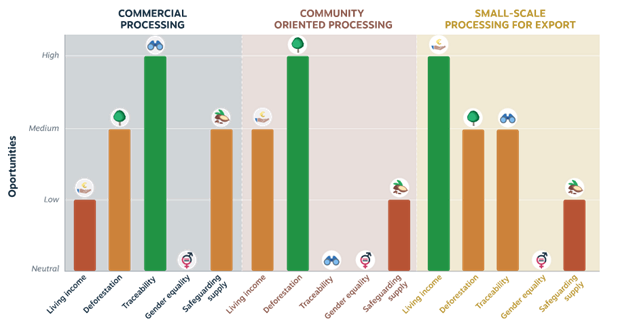

We compared the potential impacts of these three models across a selection of measures that are important to the local economy and communities. This comparison shows that the Orange CocoaPro model does indeed have high potential to support living income among farmers, although on other measures it may have less impact than the other models. This tells us that to promote positive impacts in a system, it is important to consider different potential impacts and identify trade-offs and synergies.

For more information:

Please contact the LAN-team in Côte d’Ivoire: abi-lnv@minbuza.nl

*Other frontrunners are e.g. Circle Economy, Except Integrated Sustainability, DRIFT, Netherlands Food Partnership (NFP)

Author: Hessel Moelijker, Metabolic